The latest four-day week trials show overwhelmingly positive results, but there are still question marks about the true feasibility of it becoming the new normal working week, and are there other more immediate ways to achieve the benefits that employees are seeking?

(10-minute read)

Since 2003, employees in the UK have had the right to request a flexible working pattern. More precisely, after 26 weeks’ employment, they can make a flexible working request which their employer cannot decline without a valid reason.

Fast forward to 2023, and the government are looking to reduce this 26-week period to just one day showing continued progress with the flexible working agenda. Meanwhile, in an unpredictable labour market, a way to better attract and retain talent is coming to the fore.

The concept of the four-day work week has been gathering momentum for some time. Many have joined the debate, from HR think tanks and business leaders to economists and MPs.

But in recent months, two critical events have prompted me to weigh in:

- 4 Day Week Global released the results of the world’s largest trial of the four-day week with no loss of pay (more on this below)

- Labour MP for Bootle, Peter Dowd, introduced a bill to Parliament to mandate a four-day week and legislation for employers to pay overtime at 1.5x the standard rate of pay above 32 hours per week

The time is right to ask five simple questions (what, why, who, how and when?) to understand whether the widespread four-day week is really imminent – and possible.

What is it? (And what is it not?)

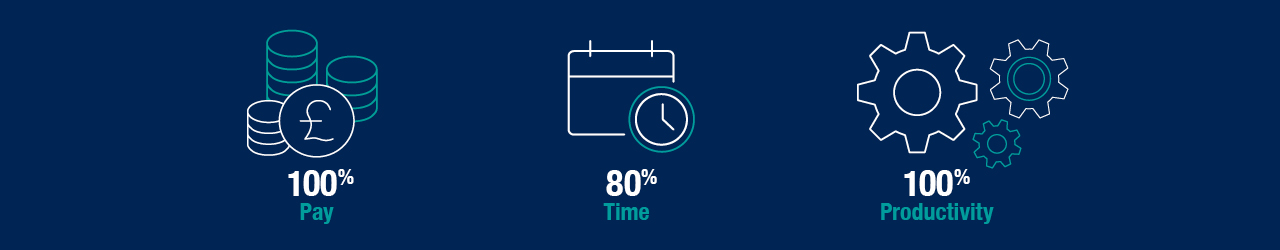

The four-day week is also known as the ‘100:80:100 model’ – 100 percent of the pay for 80 percent of the time while maintaining 100 percent of the productivity.

In other words, a full-time employee works four days instead of five, but delivers the same outputs and receives the same salary.

This is not to be confused with ‘compressed hours’, where employees work full-time hours over fewer days, or ‘nine-day fortnights’, where employees have one day off every two work weeks.

The four-day week gained traction in 2022 with the launch of the major, multinational trial mentioned above, coordinated by 4 Day Week Global in partnership with Cambridge University and Boston College. The trial involved over 2,900 UK workers across 61 companies, ranging from fish and chip shops to financial services firms.

Despite its burgeoning media presence, versions of the concept are not new, an example familiar to many was when Iceland trialled the four-day week in 2015–2019.

Why are people calling for it?

The four-day week involves working 20% fewer hours for the same pay – or, put another way, getting a 20% hourly pay rise. Who in their right mind would say ‘no’?

Indeed, opinion polls show broad support for the idea among the general public. Research by Reed in 2022 found that 89% of workers currently on a five-day week were in favour. Another study found that one in three British workers said they were actively seeking a four-day work week and would leave their job if their employer didn’t offer it to them.

But is something more going on? The same research by Reed found that job seekers were more likely to apply for a job if ‘flexible working’ was included in the ad, as opposed to a ‘four-day week’ mentioned specifically. It’s possible that workers want greater flexibility above all, and the four-day structure is just one tangible way employers can offer it.

Who would benefit?

Before the Covid-19 pandemic, any evidence of benefits was easily dismissed. Results from the four-year trial in Iceland offered some promise but, since Scandinavian countries tend to be more socially progressive than the UK, it was easy to brush this off and say, ‘it just wouldn’t work for us’.

But mounting evidence is increasingly hard to dismiss, with new studies from academic institutions and think tanks lending further credibility to the concept.

The results from the UK trial, published in February, represent pivotal evidence in the case for the four-day week. Of the 61 participating firms, 56 are continuing the four-day structure and 18 have confirmed this will be permanent. Three groups have been shown to benefit:

- Employees – major improvements to work-life balance and wellbeing, plus greater financial satisfaction, with one in five participants saving on childcare

- Employers – healthy growth and higher retention and engagement levels

- Society – boosted local economy due to increased leisure time and lower carbon footprint from commuting

The case is clear: it’s a win-win-win scenario. So why are we not all doing it? That leads onto the fourth, and probably most challenging, question being asked of the 4-day week.

How would it work?

The trial has shown the versatility of the four-day week across a range of industries, albeit on a small scale. But for many businesses, sectors and roles, there are still question marks around its feasibility.

Let’s put it to the test with a likely example.

Think about a factory that needs 100 workers on its shop floor to operate safely. If they introduce a four-day week but still require 100 workers on a given day, the factory needs to increase its total workforce size by 20% to cope with demand. That’s 20 more people to recruit, put through mandatory training, line-manage, provide with benefits and so on. This is on top of the obvious need to pay their existing workforce 100% of their salary, effectively increasing their wage bill by over 20%.

The same goes for any organisation – fast food restaurant, school, laboratory, local shop, transport company, etc. – requiring a minimum number of employees to be safe and meet customer demand.

Clearly this isn’t the case in all jobs or industries, as the trial results demonstrate – many success stories come from people in knowledge-based jobs. A shorter work week means employees use work time in a more focused way, increasing their output per hour so that overall productivity is unaffected. But the results are based on a small amount of these type of roles, meaning wider testing is needed before we jump to too many conclusions.

But in any case, in an operational workplace like a factory (or many, many other work settings), increasing output per hour safely and effectively is a huge challenge that needs to be treated carefully.

This means we run the risk of creating a two-tier workforce, dividing those who can and cannot benefit from a four-day week. This is in a similar way to the pandemic-induced divide between those able vs. unable to work from home. At the height of the Covid-19 pandemic, lorry drivers, supermarket workers and factory operators went to work without the protection of a vaccine, while others could minimise their exposure to the virus by working from home, creating a sense of divide. The four-day week could pose a similar problem. And jobs falling on the ‘right’ or ‘wrong’ side of the fence could lead to mass retraining and labour shortages.

Technology and automation are likely to play a major part in enabling some businesses to make the shift. Advancements would allow some processes to be completed without human intervention and plug the gap left by employees spending less time at work.

To achieve this, organisations would need to invest significant sums in technology whilst maintaining their existing salary bills – effectively upping their overheads and reducing their profit margins. And the companies creating automation solutions would increase their prices to reflect growing demand for their services, meaning the cost of investing in automation could rise and rise, driving total overheads up even further.

So, evidence shows that the four-day week can work, but there are significant barriers preventing widespread adoption. This brings us to the fifth and final question.

When will it become the norm?

In my view, the four-day week is highly unlikely to become a mandate anytime soon.

Aside from the practical and financial barriers, there are some attitudinal problems that need to be addressed too. Lots of employers are reluctant to have employees working out of their sight at home, let alone giving 100% of the workforce 20% of the time off ‘for free’, so it feels some way off.

Meanwhile, within Parliament, managing inflation is a critical priority. Creating a scenario where 100% of the national workforce has 20% more time to go out to shop, eat and drink, driving inflation up further, is one that few policy makers will want to enact. This is especially the case when those very places we’d be spending money would likely be having to charge us more due to their own overheads rising.

But, stranger things have happened. Around a century ago, plans to reduce the six-day week to five days faced many of the same criticisms.

The most likely and realistic scenario? The four-day week continues to gain popularity in the years ahead and becomes another way for businesses to differentiate themselves in the war for talent.

Gradually, larger and larger organisations will adopt it, including a growing list of household brands. Evidence of benefits will continue to build and strengthen. And the conversation will continue in Parliament, intensified if the next general election results in a Labour government.

But if this – the four-day week - is the big conversation, then I wonder whether we’re talking about the right thing.

The concept of the four-day week is easy to grasp, appealing on an individual level, and somewhat revolutionary. It makes for a great soundbite. But, ultimately, do people want the specifics of a four-day week, or do they just want the change it represents? Are we really calling for a better work-life balance, more financial prosperity, more flexibility and trust from our leaders, yet are simply grabbing onto the four-day week as the simplest (but incredibly hard to implement) way to achieve it in the hope that it at least forces the right conversation amongst business leaders?

Yes, of course the four-day week is one way to achieve all of those things – but it is not the only one, and therefore all of our efforts should not be on making one single idea work.

It sounds like my views on the concept are overwhelmingly negative: they are not. For the avoidance of doubt. If it has become the norm in five, 10 or 20 years – fantastic, everyone will be a winner. Employees will be happier, healthier and spending more time doing things they enjoy while maintaining their financial wellbeing. Businesses will be growing, retaining their best talent and reaping the rewards of higher productivity and a more engaged workforce. Society will be greener, more prosperous and more progressive. There are just some hurdles to overcome to get there. Here’s to hoping.

Jack Evans

Principal Consultant

Linkedin

Watch Jack's discussion on putting wellbeing at the heart of your organisation